Tuesday, May 6, 2008

Sunday, May 4, 2008

Children of God Reflective

Going along with Liz's and Phil's posts, I agree that the revolution would not have happened without outside influence, but I think it was Sophia's assimilation into Runa society which kept the revolt going. In class, I mentioned the connection I saw between Sophia and liberation theologists in Latin America, and on reflection, I think that it is a relatively apt comparison. One of the most basic reasons that liberation theology took such a strong hold in places like El Salvador was because it introduced leftist ideas as a part of the pre-established Catholic culture. This is not to say that leftist ideals about class equality and labor equity would not have caught on eventually, but by couching it in theological terms it became much easier to make liberation ideas a part of every day existence. Likewise, I believe that Sophia's shout of "we are many they are one" might have eventually sunk in for a few Runa and maybe someday there would have been a revolution. However, the fact that Sophia became stranded with the Runa, and learned their cultural ways, meant that she was able to adapt her idea of justice to fit within their cultural framework. I believe it was because Sophia became an accepted member of the Runa culture that she was able to become an effective proselytizer for justice. I think this goes along with what we discussed in relation to the Spanish in Mesoamerica. It was not the priests and conquistadors who viewed the indigenous populations as essentially Spanish in nature who were successful at converting and conquering, but rather the one who took the time to understand the culture which they were trying to interact with. Granted, Sophia's efforts were ostensibly more moral, but the principle behind them, I believe, was the same.

Look to Windward Substantive

Children of God Reflection

I relate Sofia living among the Runa with vegetarianism, kind of. She began to empathize with them, without understanding the social structure among Runa and Jana'ata. We sort of discussed what separates pets from breakfast. PTJ posed the question "does talking mean they are no longer prey?" My answer would be yes but only if the talking prey tells me to stop eating them. In the case of the Runa, some would still offer themselves up to the Jana'ata.

Windward Substinative

Unlike Tim I was not a huge fan of look to windward. I can't place my finger on anything specific--I just felt like the weapons pornesque descriptions of people things places (people that are places and things occasionally) could go on forever--and I tend to forget those parts of books pretty quickly anyway.

Back to my post. I hinted at this idea in my last post (below), but there is a certain unnatural assumption made about humanity--we, for some reason or another, view our selves as supernatural, able to manipulate and destroy that as it should be. This is a trait we seem to uniquely identify with ourselves and tend to remove from the other (even, often, when the other is human). Look to Windward had, to me, the most reasonable others because his others seemed capable of this same act of a supernatural nature. Yes, they are also unique in both their culture and physiological makeup (I will admit a giant living aware plant dirigible is pretty unique other), but unlike so many other examples of alien species we have explored the species of the Culture's universe are uniquely unnatural--they manipulate the world around them, ostracize members of their society, and have a knack for being destructive towards one another.

Again, I will grant that it was still the humans role to interfere in everything (as we love to do when serving as a hegemonic power), and the culture seemed (in a very human way) to suggest that they were solely responsible for the problems caused by this interference (you can read my previous post to see where I lay the blame for civil wars and revolutions supposedly caused by outside forces). This self as the only truly aware peoples is something we do even with other humans though, so I would not read much into it (Columbus describing the aboriginal americans along with the plants and birds--although after reading this novel you never know maybe the plants had names).

No, Bank's others are so oddly believable because they are so...well human...in that we use human to describe that odd woman folly we love to praise. They are human--disconnected with their environment, manipulative of the afterlife, destructive towards each other in a way the aliens of Alien, The Sparrow, Enders Game, and Just about anything else we covered this semester were not.

Reflection on God's Children

Admiral Perry/ the forced introduction of the west is largely credited with the shakeup of the traditional feudal system in Japan. Suddenly the Japanese realized just how "backwards" they were and felt the need to completely reinvent themselves. If we look more closely, however, the makings of an unstable society were already there--misapportioned wealth, a largely superfluous military class, and an emergent and increasingly powerful merchant class are all things that are also associated with the French Revolution and the slow demise of feudalism in Great Britain. Neither of these societies saw the sudden introduction of an outside force, yet both transformed (one rather quickly and violently) there is nothing to indicate that without Perry presence the Japanese would not have been set on a similar course.

A more extreme example is that of the overthrow of the Aztecs by Cortez. I will go so far as to suggest it was not Cortez's doing, but the internal characteristics of an unstable empire. The Romans, without the assistance of a funny looking god-like ruthless Spaniard managed to fall apart because of some of the same issues that were beginning to plague the Aztecs--Overreaching in conquest, a large number of seditious conquered peoples, and a system of ruler selection which was not designed to pick the best individual for the job (sound like any empires you can think of now). I again argue that if Cortez/Columbus/stupid spanish had not appeared the Aztec Empire may have fallen apart (either quickly or slowly) of it's own volition.

I realized that over the course of simply writing this post I have once again switched positions on my view of the Runa revolt I once again do not believe that it would have been possible without the Jesuit presence, but I believe this is because the situation was designed to mimic the ideal--the outside influence concept was taken to the extreme in this circumstance. The civilization created by Russel was so perfect for the scenario that it could have played out no other way. The VaRakaht civilization was so perfectly constructed as a ecologically feudal society that there seems to be no way of destroying it internally. It reminds me of the mistake so often made in assuming that the actions of Humans are "not natural" we assume we are somehow capable of destroying the balance of the planet because of our Moral ability to folly or something of the sort. In the same way she seems to suggest the runa and Janata are inhuman---truly other--in that they do not share this quality. Only humans were able to step in an disrupt this balance previously the society was perfect (exactly opposite of what things should really be or even how Banks portrays the Chel civil war). Not only that, but the society was also perfectly set up to be formerly balanced yet completely susceptible to outside influence. The social mimicry of the Runa makes the whole thing spread like wildfire. Yet in most earthly examples of the outside influence the civilization is already messed up enough that the slightest little disturbance from the other is enough to bring it down. THIS IS NOT THE CASE ON RAKAHT. THE SOCIETY GOES FROM PERFECTLY STABLE TO COMPLETELY INSTABLE IN JUST A FEW YEARS.

Saturday, May 3, 2008

Look to Windward Substantive

We have the Borg and the Culture, I wonder what's next?

Oh Great...

Friday, April 25, 2008

I need a life

It is cutoff in this picture, but under the RD tag it says "Burninator: TROGDOR!!" After a week, we changed it to say "Resident Dragon: TROGDOR!!"

It is cutoff in this picture, but under the RD tag it says "Burninator: TROGDOR!!" After a week, we changed it to say "Resident Dragon: TROGDOR!!" This is what my boss asked for, and he fell in love with the fireball, as well as the rest of the building.

This is what my boss asked for, and he fell in love with the fireball, as well as the rest of the building.

I did this for the preview days with Clawed. Then someone erased Mario, so I drew 4 Yoshis.

I did this for the preview days with Clawed. Then someone erased Mario, so I drew 4 Yoshis.And yes, I know I need a life and I'm a Geek. But this is my release since I'm on the all female floor.

Tuesday, April 22, 2008

4/22 Reflective

trying to explain why they should rise up by mentioning what they have on their side, but there isn't a word for "justice" in the Runa language. I think it would have eventually occurred, with the intervention of humans, and Sofia was just there at the right time, with a strong sense of justice.

Right now it mainly looks like this course, and readings, have posed the same question time and again, who are we to judge?

And remember, there may be a day in the future when the chickens rise up.

Substinative

I say this, hoping to turn it around as well, what would Sandoz have done in Columbus' situation. Would he have presumed the perfect equality of everyone he came in contact with, and assumed that he could quickly understand not only their language, but their society and culture as well? Would he have found himself prey to some hungry cannibal tribe?

Both The Sparrow and Todorov seemed to express to opposite ends of the spectrum when it comes to dealing with the other. In Children of God, Russel makes a distinct effort to convey and ideal of something in the middle. Not the same, but not unequal. Equal but different. Somehow both Columbus and Sandoz are closedminded explorers. Where both expeditions went wrong where they could have improved their crew lists would have been to be willing to accept something not expected, or to have brought someone along with the capacity to beleive that not all societies not all peoples are exactly the same.

I wonder if, given a sense of post modernism, Columbus would have been able to handle his interactions with aboriginal americans in a positive manner.

Children of God

That said, I did feel like she stretched things a bit thin in this book. There were so many characters that I felt like a lot of them were left half-developed, which was disappointing, because most of them were people who seemed worth description. Also, while I still appreciated the literary device of jumping around in time, it felt much more haphazard in this book. I suppose that has something to do with the decreased role of determinism in this book as opposed to the last one, but the jumps felt a bit more awkward in this book. At first it does make sense when moving in relative time and actual space between Sandoz and Sophia, but the few jumps she makes to the time after Sandoz left felt forced, as though she had to fit in more exposition and foreshadowing, and this was the fastest way to do it.

I agree with the others who were left a bit disoriented by this book, but over all it was enjoyable. I felt as though its ending did detract a bit from the last book, but the bulk of the two were very complementary. I'm looking forward to our discussion, and to hearing other people's opinions.

Children of God Substantive

I enjoyed how the book skipped back and forth between the three sides. Call me scatter-brained but by the time I was bored with one chapter about Sandoz the next normally had nothing to do with him.

Maybe this has to do with just my twisted logic or something, but I actually started to feel bad for Supaari.

I guess in the end I'm like Jen and Tim in that I don't really know what to say about the book.

Monday, April 21, 2008

Reflection

There was a point in class before the break where we had established a lack of individual culpability for actions of this nature. There instead seemed to be an agreed upon satisfaction with the idea that what we and todorov could do was analyze and blame the conditions and mentality created by society. And while I essentially propose that society may be the cause for many Macro events in my post the Jeans of Society , I do not beleive that this can eliminate the ultimate culpability of the individual. I find myself in a bad episode of Voyager about temporal loops because of the various deterministic paradoxes. I believe, however, that if we take Columbus, for example, that we have no evidence to suggest he acted in the way he did because society set him up to act that way, instead, his actions and comments are entirely his own, for this reason his actions can be evaluated on their own merit without assuming a societal determinism. We could make the argument that it would have happened eventually, but it was entirely on Columbus' shoulders that it played out in that exact manner and involving him. Without this I think would could run the table to arguing that everything is societally pre-determined (although I am a physical or perhaps quantum determinism myself). I will contend, at the very least, that we have a sense of free will.

Children of God

"Listen, John prayed, I'm not telling You what to do, but if Emilio brought the rapes on himself somehow, and then Askama died because of that, it's bettter if he never understands, okay? In my opinion. You know what people can take, but I think You're cutting it pretty close here. Or maybe--help him make it mean something. Help him."

At that point, "oh no, what is Russell going to do? She's going to break Emilio again". Fortunately, that wasn't the case and things turned out relatively okay for Emilio in the end, which I think he deserved.

The Emilio from the end of The Sparrow, the one who didn't know whether to hate God or believe that this was all bad luck, is still present at the end of Children of God. On page 414, Emilio and Sofia say "I was done with God" "But He wasn't done with you" "Evidently not, either that, or this has been a run of bad luck of historic proportions". He is still not sure which it is, but is more accepting of the choice.

I was reading this book of 6 word memoirs called Not Quite What I was Planning. Found one that I swear Emilio could have written over the course of these two books: "I lost god. I found myself".

Todorov Reflection

Todorov reflection

"You killed a hundred thousand people? You must get up very early in theI'm sure if Cortes kept a diary it would look like this. Even here, death is seen as an ordinary task like lunch or a shower, not something causing many sleepless nights. My point: I don't think Cortes regretted what he did because he didn't see it as wrong. Setting up the memorial at the Aztec temple on 109 wasn't an act of regret for Cortes. As Todorov says he saw the Aztecs as curiosities.

morning! I can't even get down the gym. Your diary must look odd: 'Get

up in the morning, Death, Death, Death, Death, Death, Death, Lunch,

Death, Death, Death, Afternoon Tea, Death, Death, Death, Quick shower…'"

In his post, Mike brings up why there is no such thing as a Cortes day, but we celebrate Columbus day (as a federal holiday). I looked Columbus day up quickly on Wikipedia and found that Latin America has similar holidays like Día de la Raza (Day of the Race), Día de las Culturas (Day of the Cultures), Discovery Day, Día de la Hispanidad, and Día de la Resistencia Indígena (Day of Indigenous Resistance). Also did you know that Hawaii doesn't celebrate Columbus day but Discoverers' Day (which commemmorates Columbus and Cook)? It's interesting how the United States celebrates the day in the name of Columbus while other countries mention race, culture, and the indigenous people.

Also in class, Mike's example of the mugger in NYC reminded me of the Jesuits on Rakhat inviting Suupari to dinner after he nearly killed Sandoz.

I leave with another Eddie Izzard quote:

We stole countries with the cunning use of flags. Just sail around the

world and stick a flag in. "I claim India for Britain!" And they're

going "You can't claim us, we live here! There's five hundred million of

us!" -"Do you have a flag?" -"We don't need a bloody flag, this is our

country, you bastard!" -"No flag, no country. You can't have one That's

the rule, that... I've just made up."

This is similar to Columbus naming the islands. Are there rules for taking over other civilizations? Todorov showed us how the Spaniards conquered using signs and language. They probably had a flag too.

Tuesday, April 15, 2008

Reflective 4/15

I don't expect anyone to try and understand me. I feel I can offer a different side than most people have seen, I've just learned to be the quiet kid in the back of the classroom. I don't care if you think I'm crazy or if this has been meaningless, I just wanted to get it out there.

What happened on Columbus' and Cortez's missions are sad. Conquering/exterminating another race is not "moral" but at the same time progress was made. Life is just a double-edged sword, both sides will get hurt. I would do just as Scott said, I'd rather be Columbus because ignorance is bliss. I'd rather do something I felt was right instead of doing something I knew was wrong. Wait a minute, I did the Columbus thing (doing what I feel is right) with the AUCC. I'm even hated for it, but one person can only do so much. Like the saying goes, "you can lead a horse to water but you can't make them drink."

Are we all aliens in America? Aren't the only true "Americans" the descendants of the Native American tribes?

Todorov

With relation to science fiction, if you enjoyed this, pick up Card's Pastwatch at some point. Card notes his use of Todorov, but really it's an almost exact (fictionalized) version of Todorov's ideas. It strikes me how important for both Todorov and science fiction writers how important the idea of communication is. It's interesting to compare communication in Todorov to that in the Sparrow. Todorov notes that the conquistadors were interested only in finding the Spanish equivalents to words (when they bothered at all); Sandoz moved beyond that (he notes how careful he was to find out exactly what their words meant) but he still didn't bother with all of the signs and cultural symbols. Doesn't seem like a whole lot of progress to me. Ender's Game shows the same thing, we don't understand them, so lets eliminate them (which is much easier to deal with because, as Phil's discussion of the Sparrow alludes to, they're ugly). I suppose that most sci-fi is dystopian, but its still sad to see how little we have progressed, and how little authors envision us progressing.

Substanitive Conquest

To begin I look to the chapter Cortez and signs. Over and over again it reiterates how Cortez was constantly looking for more information and not trusting anyone. Why did our group not do this. Granted, they had a more peaceful intent than did Cortez, but at least he knew not to be a fool about things. We have, on a number of occasions and a number of blog posts suggested that they cannot be blamed for something we can spot as an error in hindsight. I argue, however, that Cortez's desire to learn and understand Montezuma and the Aztecs is essentially the same idea and if he thought to do it Emilio Sandoz and Company could have been able to do it as well.

Before moving on to columbus I also feel the need to mention Cortez's position in overthrowing the Aztecs as not being all that different from the position of Sofia as she lead the Runa against the Ja'anata. The book notes how Cortez's army is essentially some spanish Cavalry and a lot of native foot soldiers who had been oppressed by the Aztecs. We even see some aspects of Aztec determinism in Ja'anata life with regards to birth essentially serving as destiny.

If one puts the two Sandoz missions to Rakat together you total the misc. reasons for which Cristobal wanted to discover as well. The second mission covers wealth while the first one looks as beauty, learning, and the glorification of God. Columbus and the Jesuits share a certain presumptive success/fatalistic outlook on the mission. Both seem to believe God is leading them exactly where they want to go. If I did not know better I would say the Russell has read this piece.

The Conquest of America

That being said, it was interesting to read after The Sparrow, which kept popping up in my mind, but how couldn't it with all the talk of Columbus and divine intervention? He saw a lot of turtles on fenceposts, or the equivalent of such back in those days (mermaids, perhaps?). But reading about Cortes and the myth of Quetzalcoatl reminded me of Paul in Dune. During that class, a long long time ago, we brought up whether Paul manipulated the Fremen's belief in a messiah. It's a little fuzzy right now, but I thought I'd bring up that.

In preparation for PTJ's question about whether the Spaniards should have and/or could have done something different, in the text Todorov says "I do not want to suggest, by accumulating such quotations, that Las Casas or the other defenders of the Indians should, or even could, have behaved differently." (172). Interestingly, he doesn't mention Columbus or Cortes and instead focuses on defenders of the Indians or those that tried to learn about their culture. However, Cortes did learn the signs, but manipulated them against the Indians, leading to death and destruction. I don't know if Columbus or Cortes could have behaved differently because we're looking at it in hindsight.

Monday, April 14, 2008

Deus vult

We made a good attempt to list 8 individuals to send on this alien mission. The picks were primarily practical because we read/saw what happened on Rakhat and mentally swore to not let that happen on this space adventure. During the exercise, I couldn't shake the thought about Gilligan's Island. If the space lander breaks, I'd want a Professor-like character who could build a radio out of a coconut and try to get the group off the planet (though maybe MacGyver would be a better choice since it took forever for The Minnow's passengers to get off that island). But maybe the Professor is not to blame. Was it bad luck that kept them stranded on the island or was is deus vult? No character seems to go through a crisis like Sandoz, doubting his faith. In fact, the show seems to lay blame on Gilligan and his clumsiness for each failed attempt to escape.

On the topic of Gilligan's Island, I found out, thanks to Wikipedia, that there was a cartoon spin-off in the 80s called Gilligan's Planet. They go from stranded on an unknown island to a far-off planet. I'd call that a very large turtle on a fence post. I think you can only take responsibility for the failed escapes so many times before adopting a policy of deus vult. That being said, casting Brad Pitt as Emilio Sandoz-- not a good idea; deciding to make Gilligan's Planet-- very bad idea for a tv show. I can handle only so many attempts to escape an island/planet. However, according to Mary Doria Russell in the reading guide at the back of the book, "Emilio Sandoz goes back to Rakhat, but only because he has no choice. God is not done with him yet." Dun dun dun. I can't wait to read Children of God and find out what happened on Rakhat since Emilio left.

Beauty and the Other

I want to return to return to the idea of beauty in defining and understanding the other Schmitt notes "The political enemy need not be Morally evil or aesthetically ugly," but I am beginning to question if, for all practical applications, this is actually true. We only briefly touched on this in class last week, but I suspect we will spend at least some time on it tomorrow (given it's apparent importance to Columbus), but I believe it is nearly impossible for humans to separate the two. Exhibit A: the propaganda poster above--what sort of message would it have conveyed if the soldier looked like the upstanding young man who was more likely to be wearing that uniform than a large ugly Gorilla? In the same sense, what would have been the reaction of the people of earth if the Reshtar's music had sounded a little less beautiful and a little more like rape. The prince is never really a prince when he looks like a frog, and the Wicked Witch can always trick the hero if she disguises her ugly worts. We keep using biblical allusions (specifically Job) see Sarah below. I think a story with even more ties is the Odyssey--Odysseus who, during the Trojan war is watched over and guided by Athena, is finally led astray by the Gods, left to roam for years before getting home. Specific to my point in this post is his encounter with the Sirens who's beautiful song is meant only as a lure. someone needed to lash Emilio Sandoz to his mast.

Refection on the Sparrow

This leads to my second (briefer) thought, which is that the church would have had a much easier time dealing with Sandoz had he been victimized in a more sanitized way. Mike talks in his post about the saintliness of Sandoz, and it seems to me that the church would have had a much easier time viewing him as good (or even saintly) if he'd simply had the good graces to be martyred like all of the others. In thinking about all of the examples of people being punished for following "the will of god" it occurred to me that while its relatively easy to glorify someone who dies in the name of god, you don't get too much press on people who were raped in the name of god. I guess death makes for better PR. Anyway it just makes me wonder how many cases like Sandoz there are out there. People who almost died for god, but didn't quite get there, and because of that were viewed with suspicion and became outcasts rather than getting their own feast days. Maybe not many, but somehow I doubt it. Either way I find myself looking forward to Russel's further portrayals of faith in the next book.

Saturday, April 12, 2008

Greed is Good :)

But maybe it doesn't always mark the "upward surge of mankind." Todorov paints a different picture of Columbus than most Americans, or myself, learn about. Basic history classes just go over how Columbus sailed to the New World, and that's it. Not that his main motivation was gold, like Todorov proves through journal entries from the man himself.

Another great line from the same movie is "Greed captures the essence of the evolutionary spirit." Columbus' expedition definitely benefited Europe, but what about the Native Americans? They didn't really go upward, they went down very violently, with the affects still manifesting to this day.

I found this a very interesting read. It most likely has to do with me being a history nut, but Todorov brings up ideas, and facts that challenge the popularly accept "history" about Columbus.

Columbus' mission was to find a route to Asia from the West, and Todorov points out how Columbus negated any argument, mainly by the natives, that challenges this. Renaming everything when it already has a name by the locals will just make things a bit worse. For those in the class that study foreign languages, you probably understand this. Most of you might think that Munich and Muechen are practically the same thing, and just because the Germans will know what city you are talking about when you say Munich doesn't mean that it is the proper name to use.

I thought Jen did a really good job pointing out somethings between Todorov and The Sparrow.

Tuesday, April 8, 2008

Reflective 4/8

I stand by my "monospecieism" being the reason that the mission failed. As we discussed in class, even the The Time Machine it is acknowledged that there are two species. Perhaps we have a leaning towards the first find? I've moved over 10 times in my life, and each time I was in a similar situation. I didn't want to do anything wrong in the "alien" planet I was on. And when someone would extend a hand or acknowledge my existence, I would stay close to them until I had established myself in the new area. Similar to what the expedition did. And in both cases, the first was "boring" and the other, physically, screams "danger" to humans. When was the last time you snuggled up with your stuffed Aye-Aye? Probably never, we tend to lean towards teddy bears, or in my case F-16s.

In the end, hindsight is 20/20. When was the last time you did something perfectly, and when you look back there is nothing you could have done better/differently? To be honest, I would take the route the military has been making since the dawn of UAVs, send them in first so there is no loss of life. How were they suppose to know the air was not toxic? Just like I said in class, just because a planet/asteroid has life, doesn't mean the environment is safe for humans.

The Sparrow

"'Not one sparrow can fall to the ground without your Father knowing it'"This was the only reference to the title I found in the book. It is obvious that Emilio represents the sparrow that falls and questions God after what happens to him. I looked up Matthew 10 verse 29 to see what followed and this is what I found:

"But the sparrow still falls" (401)

29Are not two sparrows sold for a penny? Yet not one of them will fall toVerse 31 "So don't be afraid" just jumps out for me. It's like saying "Bad things are going to happen. It's inevitable," and then all of a sudden "You have value. Don't worry". Right now my thoughts are much like Felipe Reyes' "but the sparrow still falls".

the ground apart from the will of your Father. 30And even the very hairs of

your head are all numbered. 31So don't be afraid; you are worth more than

many sparrows.

Isn't it reassuring that we'll still be quoting movies like Young Frankenstein and The Prince Bride in 2059?

The Sparrow

Just like Tim mentioned, I don't really understand why missionaries try to help people/species that don't want to be helped. Maybe I've just become fed up with Mormons and Jehovah's Witnesses knocking on my door. You'd think after having a conversation with the Mormons, who apparently graduated from the same high school, telling them how we lived in Utah and are not interested that they would stop coming to my house. I feel that is kind of the same with the mission to Rakhat. The alien species was more concerned about everything but spirituality.

Monday, April 7, 2008

The Sparrow

What kept me involved then, and many of you have commented on, is the religious/spiritual journey of Emilio, Job, or, the man who God gave everything to and then took that plus interest. I too found this especially moving--being an atheist who was raised Catholic. My second reading through--for this class--however, forced me to pay attention to something Scott touches on briefly in his post and that is the question of the other. Schmitt makes an interesting note that the friend enemy distinction is not a question of beauty, and it seems Russel almost directly confronts the idea of how beauty impacts our perception of the other. There are numerous times on earth, before they leave where it is pointed out that a race which creates such beautiful music must be good. I wonder what Sandoz thinks now. Once they are on the planet again, there is an alomst deliberate deception by Russel to lul her characters into a false sense of security because of the beauty of the VaRakahti--particularly the Runa.

I believe Schmitt would find the book especially pleasing, not because Sandoz is hirribly raped, but because the order/the mission seemed to confuse astetics (beauty v. ugly according to Schmitt) with the political. And while I don't believe the book was intended in this manner it could be easily read as a Science Fiction play on the follies of liberalsim.

If we take the idea we expressed early in class about science fiction being a means with which to critique society without doing so directly, yet more explicitly, drawing parallels between some alien or futuristic story and the problems of the world today. One could not outwardly criticize the ideals of modern liberal pacifism where friend and enemy becomes confused with civilized and uncivilized, democratic and undemocratic, good and bad. But if you create an alien world and have a group of explorers confuse Beauty and Ugly with Friend and Enemy then the situation becomes far enough detached that those criticisms are possible. They explicitly make the mistake of confusing the two and are explicitly rebuked for it. Again, I don't think that was the point, but it's a pretty intersting line of thought anyway.

Reflection of the political

Sarah points to another rather brilliant remark. On 79 Schmitt seems to perfectly predict the shifting language of US war propaganda. I wonder, however, if Schmitt would be more critical of leadership that places war on the friend foe terms or if he would be more critical of a society and a people who refuse to accept War on traditional terms--So much so that if we discover the initially established friend v. foe terms were falsified (No WMDs in Iraq for example) we quickly lose our patience for any violence. I think there is another interesting storyline in our continued love of the Death Penalty, Schmitt points out executions are permitted within his understanding of how liberalism works, but many liberal societies (including many liberal states) do not permit executions. This calls me to question Schimmit's conclusions that liberalism can not bring an end to war. I contend that true liberalism goes one step further, and that the Friend Foe we are currently fighting is actually a result of the half-committed portion of society that still likes fighting foes and executing criminals.

Sunday, April 6, 2008

Schmitt Reflection

Reflection

That being said, I did more thinking about Ender's Game. In the first two invasions, I would say the buggers are recognized as the enemy that threatens Earth's existence. But for the Third Invasion, the buggers are foes that the IF hunts down and annihilates. The conflict turned from political to personal.

Tuesday, April 1, 2008

Reflective 4/1

Ok, now that my rant is over I can continue. I really don't know what to write this time because I'm beginning to feel this class is rehashing the same topics class after class. That's the main reason I don't say alot in class, I know I've said what I've said a few times and the point of a discussion is for new ideas to come out. I'd rather be quiet and not talk instead of rehashing the same points everyday, it kind of makes the class a bit boring.

Schmitt still makes a pretty powerful point that everything can be seen as part of the political. The EU and Microsoft is a good example. The EU is consistently pursuing the suits against Microsoft in order to make an example out of Microsoft. The EU doesn't care that if Microsoft releases its source code to the public then hackers can get into your computer no problem. That's the main reason Linux isn't a popular Operating System, because its an open source OS (in other words you can google the source code and see the actual code that makes up the OS).

Schmitt

On a probably slightly less fruitful note, the historian part of my brain wouldn't let go of the fact that Schmitt ended up being a Nazi. I realize that circumstances and moments in history sometimes sweep people along with them, but it was really disturbing to me that someone who could so clearly visualize the dangerous shape that politics could take when the enemy became "an outlaw of humanity" (79) would be a party to the atrocities of the Nazi party.

Political?

The Concept of the Political

The buggers are the perfect example of the other (or enemy when compared to humans) because they are "existentially something different and alien, so that in the extreme case conflicts with [them] are possible" (27). In Ender's Game, the IF saw the situation as us versus them, friend versus enemy, kill them before they kill all of humanity. However, I think Schmitt doesn't see it as black and white. On page 27 he says "the morally evil, aesthetically ugly or economically damaging need not necessarily be the enemy". Being classified as the enemy doesn't mean all the negative aspects of other antitheses apply. Especially since on the other side of the fence the roles are reversed. Schmitt goes on to say that the friend-enemy antithesis is not fixed and "in no way implies that one particular nation must forever be the friend or enemy of another specific nation" (34). Here's where I think the IF made a mistake in assuming that the buggers would only ever be their enemy and set out to negate their existence, as Schmitt would say.

And along with the bugger wars, Ender's Game looks into Earthside relations with the hegemony and Warsaw Pact. But I'll save that for after class, where I hope to understand Schmitt's concept a little better.

Monday, March 31, 2008

The Concept of the Political

And I totally agree with Schmitt saying that confusion arises from the concepts of Justice and Freedom being used to legitimize political ambitions or demoralize the enemy. These concepts are loosely defined, one man's justice and freedom might not be another's. Just look at Shari'a law, that's justice and freedom for some Muslim countries, but to the West it is repression. You can even look at authoritarian states if you want to stay away from religious issues, North Korea doesn't have its laws revolved around the tenets of a religion, unless Kim-Jon-Il-ism counts.

And to be the "devil's advocate" here for some of the numerous discussions we've had on morality and the like. Its all our faults for not taking the time to truly understand our "enemies"

and "allies." Everyone has blame, but one side or factor will make a choice and live with it. Hindsight is 20/20 after all, and I'm sure everyone has regrets about mistakes they've made with people, or the lack of understand of the "enemy."

Ender's Game

Over spring break I read one of Card's other books, Pastwatch, in which Card explores the first interactions between Columbus and the natives on Haiti. In that book it becomes apparent that Card blamed the failed communication between Columbus and the native people for many of the wrongs of our society and the future society he was envisioning. However he also envisioned a past in which the natives of Central America had developed the technology to fight back, and the results were as disastrous as the encounter in our time line. However, in both of these cases Card presented the conflict as a problem of the past, one which the people of the future acknowledged and were actively working to correct. I'm not sure how much of that has to do with viewing conflicts retroactively, unfortunately that is the position we're all put in whether reading history or novels. It's also difficult to put ourselves in the position of truly not being able to communicate or understand another civilization. However, that being said, I find it very hard to accept that the complete destruction of an entire species was the only option for the IL. Of course I'm not sure that I could have done anything better than the IL did with the information they had, but it seems like there should have been a better way.

Also for anyone familiar with Babylon 5, I couldn't help but compare this encounter to the initial encounters of the humans with the Minbari. Due to a miscommunication, they entered into a war which almost destroyed humanity. I guess this is a fairly common theme for science fiction. It seems that in 500 years would would have a better way of doing things, but baring a way to communicate I have to admit I'm really unsure what that is.

Sunday, March 30, 2008

Ender's Game Reflection

Does survival mean needing to exterminate the "other"? I'm all for building up defense to ensure humanity's survival, but I don't think the IF had to go hunt down the buggers and eliminate an entire race. It's as if the IF said "You know what, it's been long enough. They have nothing to offer us. Let's show them who the superior race is and destroy them". Again in chapter 15, the bugger queen says they never returned because they realized humans were sentient beings. However, the IF never acknowledge the bugger race as sentient. The closest they get is when Mazer says " In all the bugger wars so far, they've killed thousands and thousands of living, thinking beings. And in all those wars, we've killed only one" (270). Only the queen is recognized as a sentient being, and yet that doesn't deter them from attacking as it did with the buggers.

Overall, I don't believe that the IF was justified in its actions. It had acted as if attacking was its only option, refusing to acknowledge other possibilities. If I had to make this decision, I would've felt better knowing that I did everything I could before turning to ultimate destruction. Or maybe I'm being too sympathetic to the buggers. I would not have made it through Battle school.

Thursday, March 27, 2008

The Genes (Jeans?) of Society

I also believe a good argument can be made against the decision of the I.F. First, there is no reason to assume that we could beat the buggers at their homeworld--given this case we could have simply provoked another attack. Second, this left us totally defenseless should our ships have passed in space or something, while we had no idea about the overall strength of the bugger civilization. Third, it must be assumed that any commander capable of defeating the buggers in their turf would also be able to defend out turf--Ender, our weapon of choice, could perceivably serve either an offensive or defensive role. If, we assume that we must prepare for what is essentially the worst possible scenario in which it is possible to survive then leaving the fleet home would have been the best (if not the only) option. The only reason to send a fleet to attack if we assume that they are going to attack us soon would be one of vengeance, since without communication the deterrence idea of "if you kill us we will kill you" does not work.

Thursday, March 20, 2008

Tuesday, March 18, 2008

Reflections on Class Discussion 3/18

Maybe the buggers never deliberately attacked a civilian area, but humans have in the past to their own. Does that make us a lesser species?

Monday, March 17, 2008

Ender's Game Reflection

I also read this at the same time as I was reading Pastwatch: The Redemption of Christopher Columbus, also by Card. When looked at together it really struck me how much easier it is to deal with an other who is an alien rather than an other who is human. The people of Earth have absolutely no doubt that the Buggers are evil and should be eradicated. Ender points out during the trial of Graff that people called him a cold blooded killer for the murders of Stilson and Bonzo, but that no one saw killing billions of Buggers as a crime. It wasn't until Ender became Speaker for the Dead that there was any indication that people saw the Buggers as anything but a deadly pest to be eradicated. It was much harder for Card to deal with human others however; he couldn't have easily looked at the native peoples from Columbus's perspective, it would make most modern readers incredibly uncomfortable to be expected to sympathize with a main character who saw other people as subhuman pests to be eradicated or exploited. Instead, that book had to be set from the perspective of enlightened historians from the future who could see the errors of Columbus's ways. Had Columbus encounter aliens rather than people however, the book could have been written from his perspective, rather than by people observing him. Condoning genocide of something that looks completely different from us is much easier for most readers to swallow. Don't get me wrong, I'm sure that Card had other reasons for writing Pastwatch as he did, but even if this wasn't in his mind, I think it's relevant to themes we've been discussing.

Ender's Game and Shadow of the Hegemon

I also wasn't that surprised that the "games" were real. I actually expected it before I even picked up the book when Professor Jackson mentioned that there would be a big shocker in the story. Maybe I'm just jaded from my military upbringing, that in war everything is possible. I haven't seen the tactics used in the novel in real life, but we do have simulations like Red Flag in Nevada that are pretty darn real. As my Dad has told me combat is the best training possible. Both really interested me. I loved the tactics and strategy I could easily see in Shadow, as it was countries fighting each other not humans vs buggers.

The whole Battle School concept isn't that far off to me. We have military academies at West Point, Annapolis, and the Air Force Academy in Colorado. There are War Colleges in Kansas and Virginia, for example, where military officers from the US and abroad come to study tactics and battle strategies. I can't tell you the number of times I've seen my Dad writing papers on past conflicts, some as currently as the Kosovo Campaign of 1998. We even have auxiliaries of all the branches for young kids to get involved with. Taking kids at 6 is extreme, but you can join one of the auxiliaries when you're 10.

Substinative, Ender's Game

Another major theme within the novel is the idea of a balance of empathy and ruthlessness. Peter is seen as too violent and closed to have the empathy necessary to understand the bugs in order to defeat them. Valentine is too understanding, she is unwilling to kill, and Ender, of course, is the perfect balance between the twain--Violent when necessary, but capable of understanding his opponent. Interestingly, the book also seems to suggest that humanity fall more in line with Peter--more interested in destroying the bugs outright than understanding them in the slightest. I find this especially interesting since one must assume that humanity contains a mixed cast of characters, some like peter, some like ender, and some like valentine. Yet the result Card portrays is not a balanced society like ender, but an extraordinarily violent one more like peter.

Sunday, March 16, 2008

Ender's Game

Which brings up genocide. It became clear that wiping out the entire race of buggers was genocide, but no human ever said "this might not be right" until Ender had already killed them and was acting as Speaker for the Dead. Humanity's excuse for genocide was self-defense, us or them, the best defense is a good offense attitude. Why rush into exterminating an entire race? Aside from the timing of the ships arriving near the bugger homeworld, could it be related to Ender's age? Would it have been harder to lie to Ender about the simulators if he had been a year or two older? If he had killed the buggers sooner, would it have not affected him as much?

Friday, March 7, 2008

V reflection

I also continue to wonder just how much control V had over the situation. We bounced around this question a couple of times in class with regards to moral issues, but I wonder if planned out every single thing, knew how people would react and worked to create the "environment" that would cause that reaction, or if there was actually some element of chance or free will. Yes, V just put Evey in the right environment, but if he knew what would happen then he made the decision for her. It's especially telling that he controlled fate--he had the power to manipulate destiny, to predetermine how things would occur. In a sense, this is even greater power than Paul's as he could only see the future, while V writes the future.

V for Vendetta Reflection

Lincoln is one of our most notable presidents and idolize him because he kept the country together in a time of crisis. The American public doesn't care what he did to ensure unity; only the end result matters. V is not as idolized as Lincoln. In class, we weren't able to come up with an answer whether V was good or bad? His goal to end fascism in England is admirable, no matter what his intentions might be. Machiavelli's "the ends justify the means" rules the exceptional circumstances. However, Adam Susan comes off differently compared to Lincoln and V. Fascism is the means for Adam Susan. But what are his ends? Is it purity? He's pretty much obsessed with purity. We don't see how he rose to power so we don't know what was necessary for him to do. To us, the fascism isn't justifiable. Add to that, Moore makes him look crazy by falling in love with Fate and it's even harder for us to understand him.

Reflection on V for Vendetta

Also, with regard to whether or not V is a "good guy" I would argue that he is not. I'm not even entirely convinced that he is the protagonist of the novel, I found myself feeling far more interested in Evey's character, if only because she was much more three dimensional. I believe someone mentioned that while V is represented as the antithesis of Norsefire, which is decidedly evil, being the antithesis of something evil doesn't automatically make him good. That said, I'm not sure that V is as antithetical to Noresfire as he would like to be. Like Norsefire, it seems as though he has decided that he alone gets to determine who is human enough to be worth saving. For the government, that was people of the 'Nordic race,' and for V it was anyone who hadn't been too contaminated by the government, and even then he may have set those who might be worth saving on a path to destruction, unless they could find a way 'free' themselves after he created mass chaos. Also, in his treatment of Evey, it seemed that he was trying to mold her in his image by subjecting her to the same treatment (minus Batch 5) that he and Valerie had been subjected to. While he may have felt justified in do this, he did to her exactly what the scientists at Larkhill had done to him, which really puts them on the same level in my opinion. I'm sure that those scientists felt just as justified as he did in performing their experiments, and equally sure that V wouldn't have hesitated to kill Evey had she not passed his test. While there is the chance that V's actions produced more positive results than the actions of those in power, I don't believe he occupies the moral high ground in any way.

Wednesday, March 5, 2008

V for Vendetta

I found V for Vendetta quite good, and better than the movie like the Professor mentioned. I enjoyed the part where V blew up the Justice statue as well. Just like Philip pointed out, I don’t feel the graphic novel is about anarchy. It was more chaos than anything else to me. I might be bias when I say I like the graphic novel format better. There are just some little details you can’t get with a normal novel that you get in V for Vendetta. I found it quite easy to follow along from the numerous manga I have read before.

On a random note, I was so thinking about Captain Planet when I noticed that V’s epiphany was true fire, Evey’s through water and Mr. Finch through LSD (let’s just call that “heart”).

I can’t remember what page it was one but I remember Mr. Finch saying that the Leader did not heal the wounds from the war. After the Leader was dead, the country went to chaos. Sounds like the Balkans to me. Tito was a fierce dictator and kept everyone in line until he died. Now look at all the wars in the Balkans.

Now for my reflection, It seems the question of why V gets to do as he pleases is a common thread amongst all the reflective posts. I think he is allowed because the citizens were upset with their current situation and were powerless to do anything. Then V came along, blowing up buildings, giving them 3 days of no government surveillance, and giving them a choice of what to do. I had to sit in a chair watching the wall for 2 hours during a polygraph test today and it sure felt better getting out than when I was answering questions. When the interviewer asked me the questions without the equipment attached I was fine, but once everything was hooked up I was a bit scared. Perhaps the citizens felt the same.

I think the bottom line is you see what you want to see in the story. In my book V is neither a good guy nor a bad guy.

What really strikes this as a power graphic novel in my mind, is the idea of this fascist state is not far out there. It happened before in Nazi Germany, whats to say it won't happen again?Tuesday, March 4, 2008

V for Vendetta

I thought one of the more interesting devices in this book was the use of all of the varied cultural references and the use of music. V quoting Shakespeare (11-12) and the Rolling Stones (54) with equal conviction and I am Legend sitting on V's bookshelf next to Dante (18) made an interesting point about the importance of any culture, not just "high" culture. Also the set up of Book 2 with a song was an interesting way to give an overview. I also really appreciated the Les Miserables reference on 255, especially after seeing the way Finch's obsession with V played out. There are definite parallels to Lean Valjean and Javert, but I didn't think of them until seeing the graphic.

I found pieces of the premise somewhat hard to believe, but that may have been because of the time the novel was written at. While I can accept the idea of Britain becoming a dictatorship, the idea of it being religiously based is pretty hard to believe. Beyond that this book was decidedly a product of the Cold War, which doesn't diminish the value of its commentary, but should be taken into account, and does take away slightly from its verisimilitude.

On the other hand, the idea of a big brother society is still alive and well long after the Cold War. There are already cameras in almost every city in Britain (which look identical to the ones on page 9) which constantly monitor looking for criminal activity. Some even have live operators which inform people when they have been spotted littering or engaging in "anti-social behavior" (check out the BBC's article). I found the concept a bit creepy while I was living there, but almost everyone took them for granted, and seemed completely oblivious to being monitored. While it's probably not a slippery slope, the possibility seems to exist, and keeps this novel very relavant.

V for Vendetta

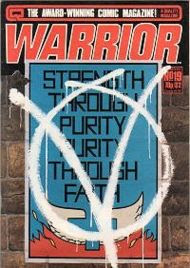

But while reading V for Vendetta, I was looking for the differences, kind of like those spot the differences cartoons. The overall picture is similar, but there are 10 or however many minor differences. I'm not going to name all of the differences, but one visual difference I saw was Norsefire's slogan. In the graphic novel, it was "Strength through Purity. Purity through Faith", whereas in the movie it was changed to "Strength through Unity. Unity through Faith". (See the pictures below)

The film tried to slim down this complex graphic novel and in that attempt left out certain details and failed to acknowledge secondary characters. It's not that the film left out everyone, though the wives are missing in the film, but it passed by them so quickly I couldn't catch their names so I never thought they were as important. I think there will be enough ranting about the movie vs. graphic novel in class.